Have Gruelling Schedules Caught Up With the Top of Men's Tennis?

Andy Murray’s withdrawal from the Australian Open topped the list of a series of unfortunate absences to start the men’s 2018 tennis season. Are the physical demands of the current game causing burn out at the top of the sport?

After some of the biggest names in men’s tennis— Novak Djokovic, Andy Murray, Stan Wawrinka, Kei Nishikori— were forced to cut their 2017 seasons short due to injury, many were looking to 2018 to be the year of the comeback. Now one week into the 2018 season and it is looking like the depletion of the top of men’s tennis might be the new norm.

Though Nadal, Djokovic, and Wawrinka are still set to play at the 2018 Australian Open, the withdrawals of Kei Nishikori and Andy Murray, who haven’t played a competitive match in 5 and 6 months, respectively, signal a troubling shift. In today’s game serious injury is no longer the bad luck of a few players, it is an epidemic at the highest levels of men’s tennis.

But, if top players are now at greater risk of injury than they have been in the past, what could be the cause?

We are not likely to find any one cause for something as complex as injury in sport but to find at least one of the major contributors we can look to one of the major complaints among top men in recent years: their gruelling schedules. For a number of years, the biggest names on the ATP have raised concerns that fitting in 4 Grand Slams, 9 Masters events, and (typically) 10 or more lower-level events (not to mention Davis Cup and Olympics when those opportunities are there) has left them with virtually no off season.

There is bitter irony in the fact that Andy Murray has been one of the most vocal about the grind of the current tour.

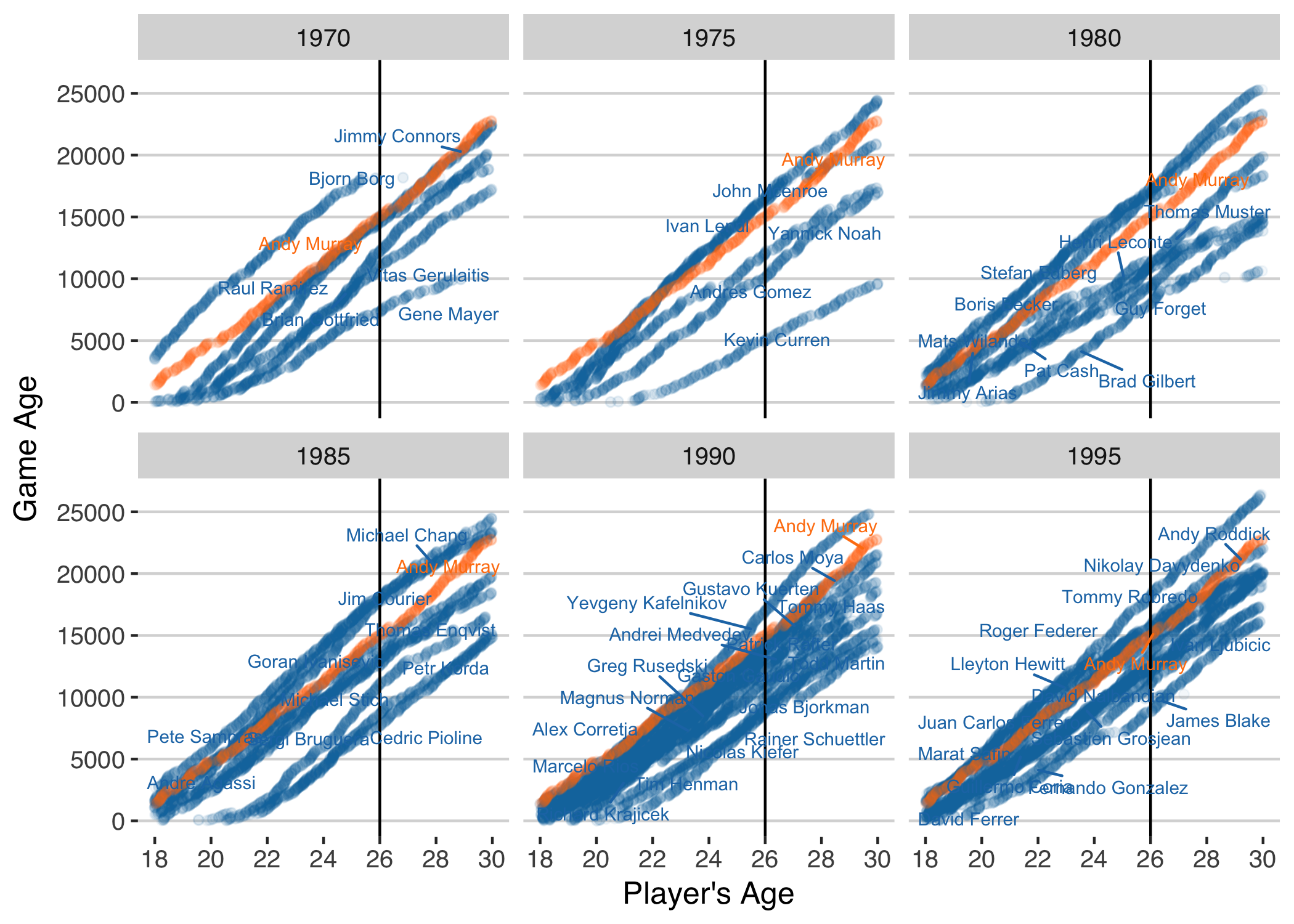

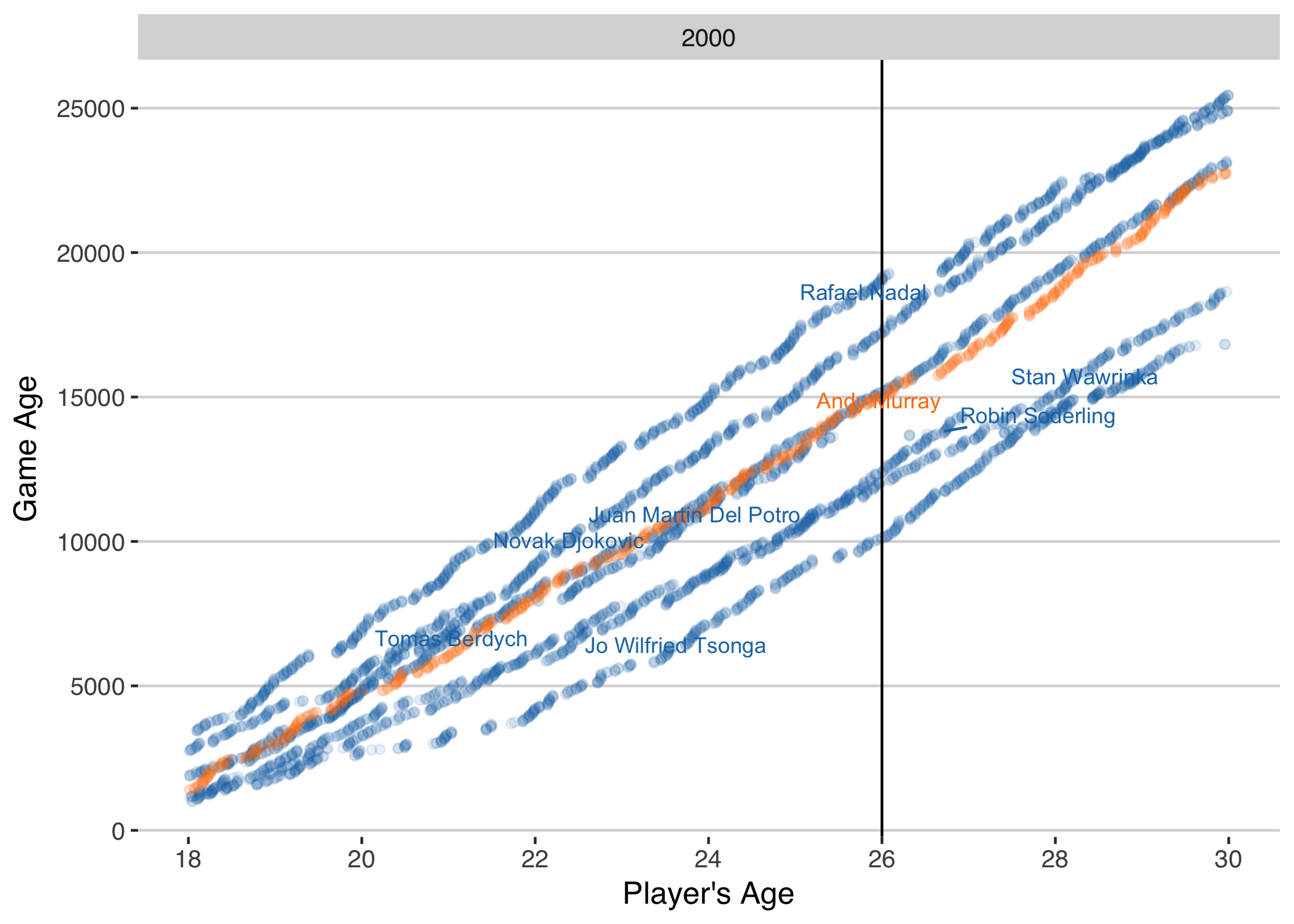

The difference in Murray’s game age compared to earlier generations backs up his concerns. The ‘game age’ is the total professional games played by a specific calendar age. The chart below compares Murray’s game age (in orange) from ages 18 to 30 years and compares it to other top 5 players from previous generations beginning with 1970 (here a generation is determined by the year a player first entered the pro tour).

Consider how Murray’s game age compares with the top players of the generation of 1970 (top left). Murray’s game age is far ahead of the pack, tracking Jimmy Connors' rate of games played, a player who was an outlier of his era for playing an insane amount.

Only one of the top players in the 1970 group clearly exceeds Murray’s game age: Bjorn Borg. Borg burst onto the scene as a teenager, winning his first Grand Slam at 18 years old. From then on, his success over the next 8 years caused his game age to skyrocket. By 26, Borg has accumulated more than 18,000 games played, 2,000 more than Jimmy Connors. While Borg was considered young to retire at 26, in terms of his game age, it was perfectly normal.

Murray’s comparative competitive wear relative to early generations wasn’t limited to the 1970s. If we look across the years, we see that Murray’s game age has been ahead of most of the top players of the past. It isn’t until 1995 that Murray’s game age looks more typical.

When we look at how Murray compares with his own generation, we see that his game age is fairly typical of the top of the game. This fits with the conclusion that the ‘grind’ of the tour has become a widespread phenomenon and not simply the bugbear of a select few.

All of these trends make Federer a bit of a puzzle. At least on the surface. By age 26, Federer (like Borg, interestingly) had played over 18,000 games. Murray, by contrast was just over 15,000. How with so much greater comparative wear has Federer escaped the kind of repeated injuries of a Murray or Nadal?

We can’t ignore that ‘competitive wear’ is more than just games played. The length and intensity of those games matters hugely for the physical effort a player exerts. So 1 game played by Murray today may have a much higher physical cost than 1 game played by Jimmy Connors in 1975 or 1 game played by Roger Federer today. In fact, my analysis at Tennis Australia’s GIG shows that Andy Murray performs more work per point than most top players.

If the 2018 season follows the same pattern of 2017, as it appears to be shaping up to do, the problem of rising game ages will be an issue the men’s tour can’t afford to ignore.

The data and code for this post can be found here.