What Can Match Stats Tell Us About Playing Styles?

Recently, I’ve had a few posts on head-to-head effects. The biggest takeaway was one we probably all knew going in: Head-to-head effects may exist, but good luck finding them. With so many small sample sizes for most head-to-heads, we need a way to group ‘similar’ players. In this post, I look at whether categorizing players by playing style might be possible using basic match stats.

When Roger Federer faced John Isner in the finals of the Miami Open last week, many in the tennis world were surprised to find that the two had not played each other in a tour-level event since 2015. But infrequent meetings among top players is more the rule than the exception. It is one of the unfortunate realities of the structure of professional tennis (though, honestly, I am not sure I would want to see Isner play that much in finals).

Sparse head-to-heads are also one of the banes of existence for tennis modellers. We are often tantalized by the idea that ‘matchup’ will give us that extra boost to our performance models only to struggle to find a way to reliably measure these elusive effects.

In statistics, there is a common concept of “borrowing strength”. This is the idea that we can learn more about what a piece of data is when we look at it with similar data. It sort of like when you seeing family members side-by-side you realize that it’s that nose or that chin that makes them so distinctive. Pooling similar data in statistics can have the same end—helping us see more clearly what are a thing’s defining features. This is exactly the kind of solution matchup effects in tennis need.

If pooling is really about putting similar players together, we need to have a way to gauge player similarity. What would it mean to say two players are similar? Well, it could be any number of things. But, if our purpose is to understand matchup effects, we really want to focus on players with a similar playing style.

The difficulty is no one knows how to quantify style. Like so many of the most interesting parts about tennis performance, style is one of those things that we know exists but we just don’t know how to measure it.

Ideally, style would take into account a player’s shot choice and results with each shot type. But even those basic elements aren’t something we can easily get at with public data, at least not consistently for most top players.

Basic match stats— first serve in, return points won, etc.—are the most detailed information we can get for the majority of matches and professional players. For the most part, these would seem pretty limited in what they could tell us about style. Most match stats are most directly related to a player’s relative ability compared to their opponent on the day.

But, for helping to categorize style, would it be too hasty to write off match stats entirely?

I am not so sure. There are some measures in there after all, like aces and double faults, that are products of a player’s serve technique and risk-taking that should in theory be under the control of the server. Match duration is also another match stat that should be closely tied to how much a player likes to rally.

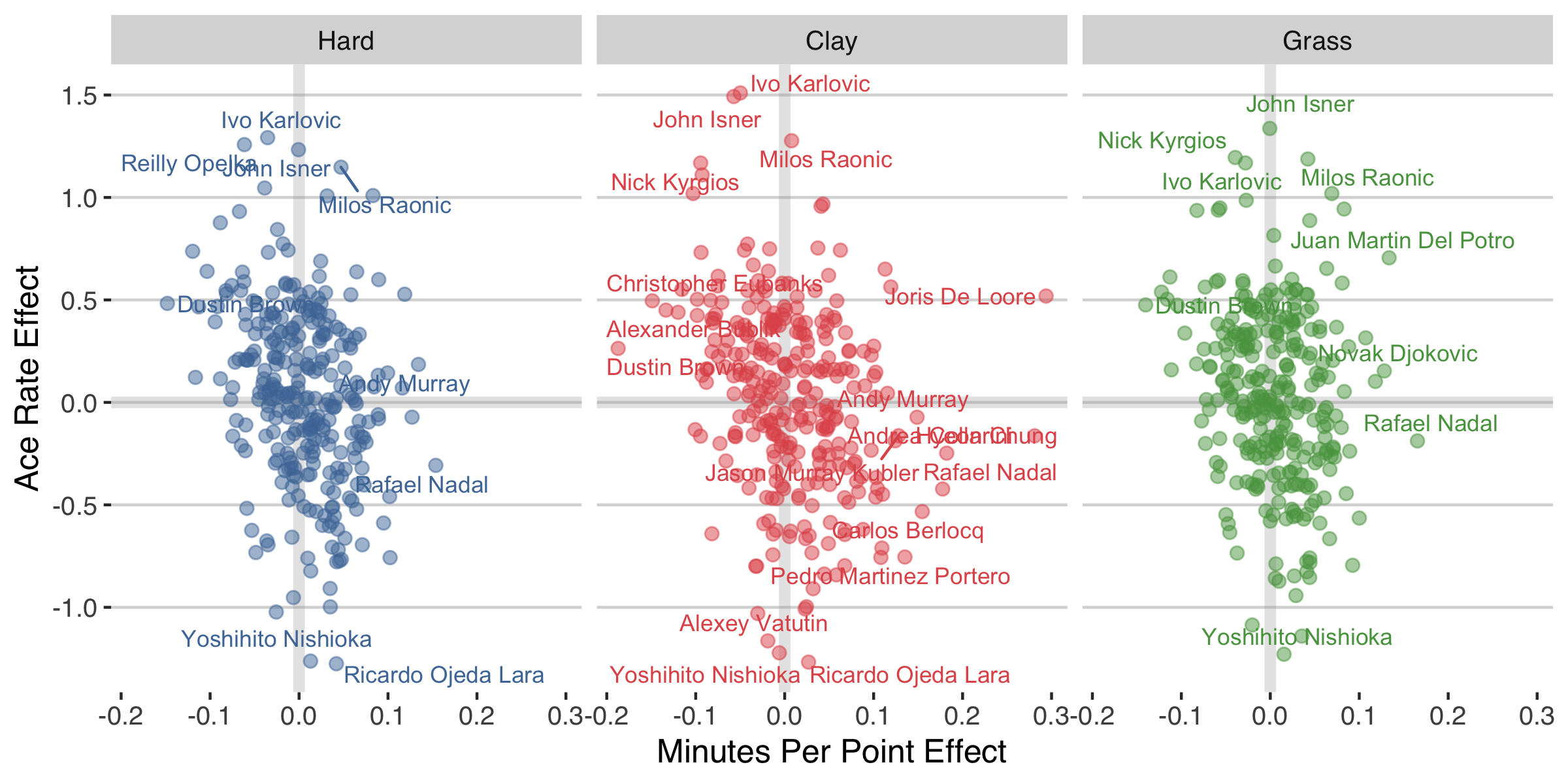

As an initial experiment, I took a look at what ace rates and minutes played per point might reveal about player similarity. Because we are interested in a player’s tendencies apart from their opponent’s', I’ve used a mixed model to calculate an average rate for each player on each surface for matches played since 2017. I’ve limited the sample to players who made appearances and two or more Grand Slams, so thought it should give a group that has seen a similar mix of opponents over that time period.

Here is what we find for ATP players. The first thing to notice is that there isn’t a strong correlation between the ace and minute effects. I went into the analysis thinking that players with an above average number of aces per points served might also play quite quickly. Although that is the general tendency, the relationship is fairly modest.

I’ve highlighted the 2% of effects that are the most extreme. On the high-end of the ace rates, this picks out the usual subjects: John Isner, Reilly Opelka, and Ivo Karlovic, for example. That confirms that the ace rate effect seems to be doing something sensible in getting at the overall power of serve and not simply overall winningness on serve, as, for example, we see Rafael Nadal below average in the ace rate category despite being one of the most effective at winning points on serve.

Yoshihito Nishioka is on the opposite extreme in terms of aces. At 5 ft 7 in, Nishioka is much shorter than the average slam player, which could account for his position in this chart.

In terms of minutes, it is notable to see Andy Murray, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic appear among players with some of the longest durations per point. This is consistent with their characterisation as grinders. On the other hand, players who play unusually fast and aren’t among the biggest servers include Dustin Brown and Florian Mayer. These could be examples of players with an aggressive style of play whose serve isn’t a huge weapon.

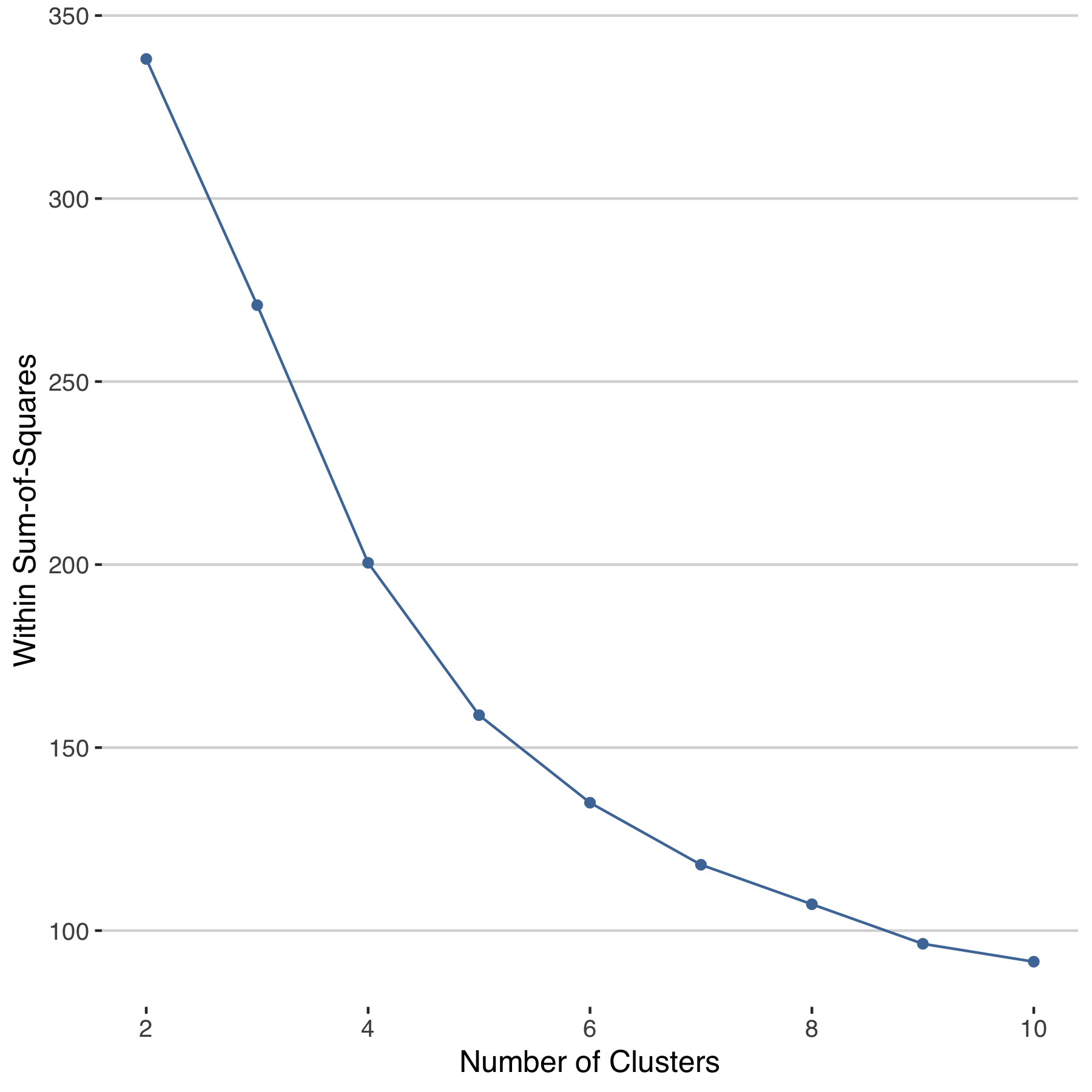

The extreme cases point out some players that are more like some than others. We can get at this in a more systematic way with clustering. As a simple start, let’s consider what a k-means clustering on the hard-court effects would suggest. The pattern in the error within cluster suggests that six groups would be the least complex way of cutting up the data to get close to the minimum within-group variance possible.

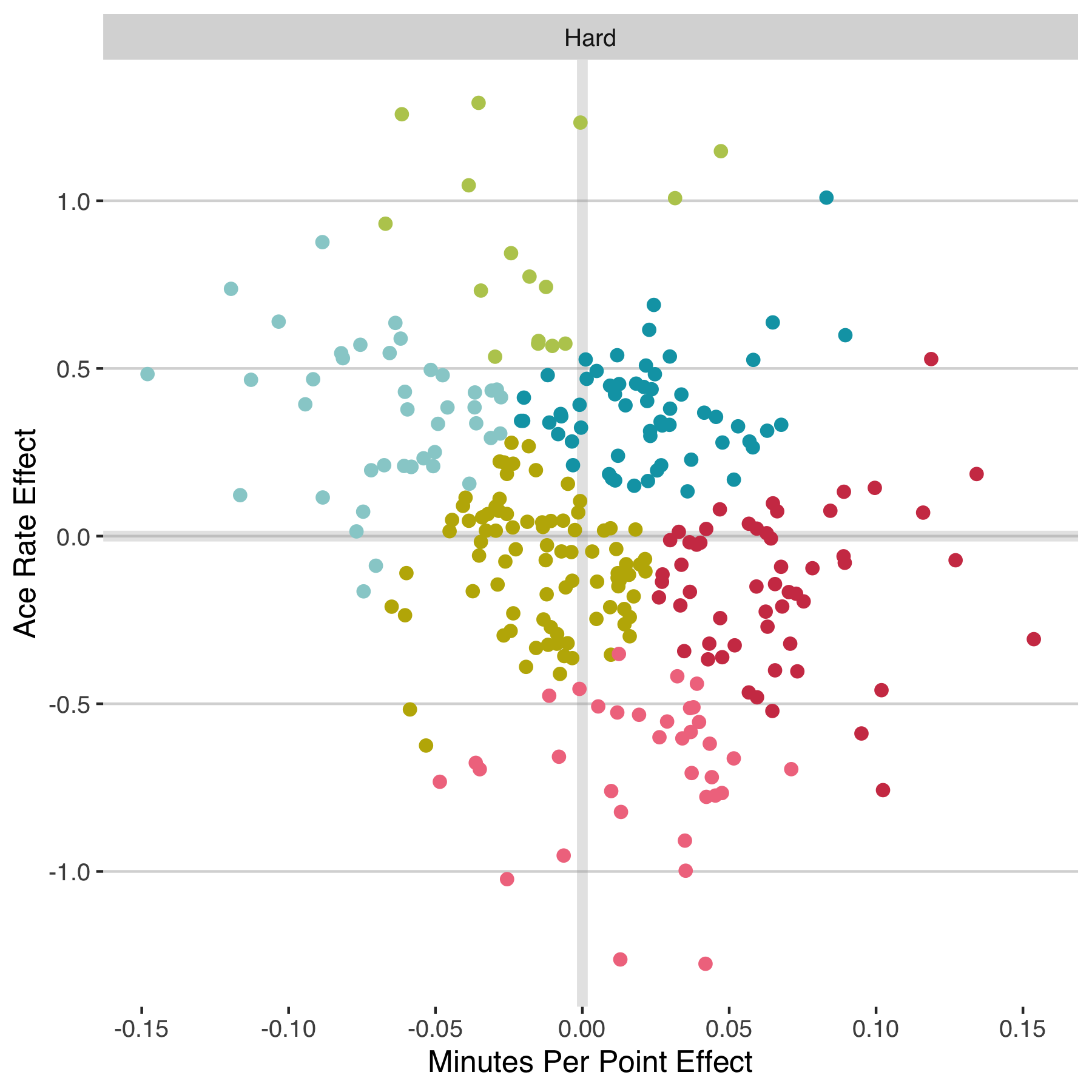

The figure below shows how those clusters would relate back to the ace rate and minutes played effects. It shows well-separated groups that would could easily give a meaningful label to, in terms of their particular combination of intimidating serve and pace of play.

Two attributes isn’t enough to get at all the nuances of style we would like to. This has been only a small experiment, but I think it reveals some promising possibilities. Can we classify all facets of style from basic match stats alone? Probably not. Can we classify some major categories of style? Maybe. At least, I am more convinced of that possibility now than I was before seeing these results. Which means there may yet be hope for a style-based approach to estimating matchup effects.